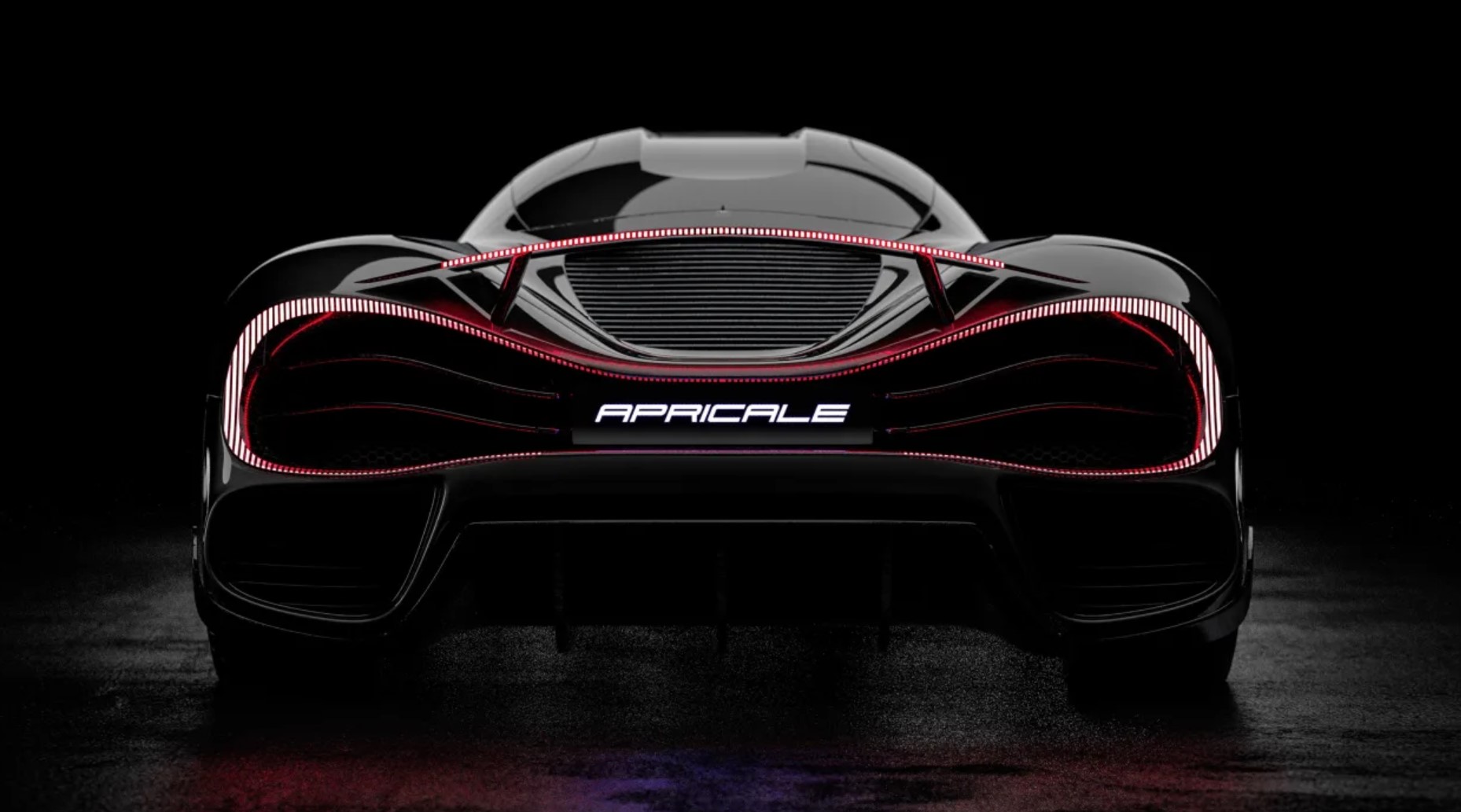

This is not another heavyweight battery-electric hypercar, rather it’s a showcase for a new hydrogen fuel-cell technology that can deliver 900kW in a car that’s as light as an Elise.

I know what you’re thinking: another swoopy, extremely high-powered hypercar, costing megabucks, from a brand you’ve never heard of. And you guessed right, it has indeed got a battery and there isn’t a petrol-powered engine in sight. But I promise you that reading on is worthwhile, because what you’ll learn about might, just might, be the saviour of those sorts of cars.

One of the key people behind it is Matt Faulks, former boss of racing car support and development specialist Tour de Force. I always make a point of answering the phone to Faulks, not least because he once offered me a drive in an F1 car before Saturday morning practice at the 2018 Belgian Grand Prix, and as ludicrous as it still sounds to me, it actually happened. So when he said he’d started an entirely new project with a long-standing friend back in the lockdown winter of 2020, and that it was going to produce a car that featured over 750kW but, crucially, weighed similar to a Lotus Elise, and that it might in its own way help save the planet too, it clearly sounded like something we should know more about.

The new company behind the project is called Viritech, and the car is the Apricale. It is powered by a fuel cell that converts hydrogen into electrical energy that then drives electric motors, but the car also features a small, F1-style battery that supplements the fuel cell’s efforts as required. Because the car doesn’t lug around a huge battery pack its weight is comparable with an ICE sports car’s, yet its power output is even greater, while in ten years the technology as a whole is predicted by key industry players to be on a cost parity with ICE, too.

Even Lotus, which claims its Evija battery-electric hypercar is the lightest of its type yet, hasn’t been able to claim a kerb weight much below 1700kg, and therein lies the point. Faulks hates heavy sports cars, and heavy racing cars too for that matter, and refuses to see a future made up almost entirely of two-ton, huge-power but arguably soulless hypercars.

But there’s the Apricale and then there’s the much bigger picture. ‘We’re not here to set up a sports car brand,’ reveals Faulks, Viritech’s CTO. Instead there will be just 25 Apricales, and while they will be supported with further developments in the future, the car is effectively a shop window for the technology, because let’s face it, attracting headlines is much easier with a hypercar than it is a new truck. And why not a spiritual successor to the Lotus Elise? Because new technology is expensive and economies of scale further down the line will be required before more affordable sporting machinery can realistically be made.

Rather than aspiring to be a car maker, the business is based around two elements. Firstly, to offer a green solution to low-volume, UK-based manufacturers who need a low-emissions powertrain but don’t want to be battery powered due to their brand being about light vehicles. And secondly, to license the patented technology to OEMs and Tier 1 suppliers, making it available to all who are willing to pay. Principally, that’s the LCV and HGV market, where the restrictions of range and weight (versus payload) are presenting huge problems.

It’s not true to say that Faulks hates electric cars. He describes the Nissan Leaf as ‘brilliant – but boring’ and believes that in the very near future our motoring lives will be dominated by battery EVs for urban and general driving. And that, he says, is fine. But what he doesn’t believe is that the BEV is the answer to all our future transportation needs, and increasingly others are coming to the same realisation.

‘Myself and [Viritech co-founder] Timothy Lyons go back a long way,’ says Faulks. ‘We were bored in lockdown and kept talking about what we could do together, and Timothy eventually suggested hydrogen. I replied, “I think we can lightweight that.”’ Just a week later Viritech was born, and progress since then has been nothing but rapid. An initial round of private equity exceeded their expectations and the firm is now 12 months ahead of its original schedule, with the first mule car built, a headquarters based within the famous MIRA complex near Nuneaton along with access to MIRA owner Horiba’s extensive facilities and hundreds of engineers, a rapidly expanding staff, and relationships with most of the required major suppliers. And that’s not to mention Faulks’ work with governmental departments and other bodies around the implementation of hydrogen as a viable fuel for the future.

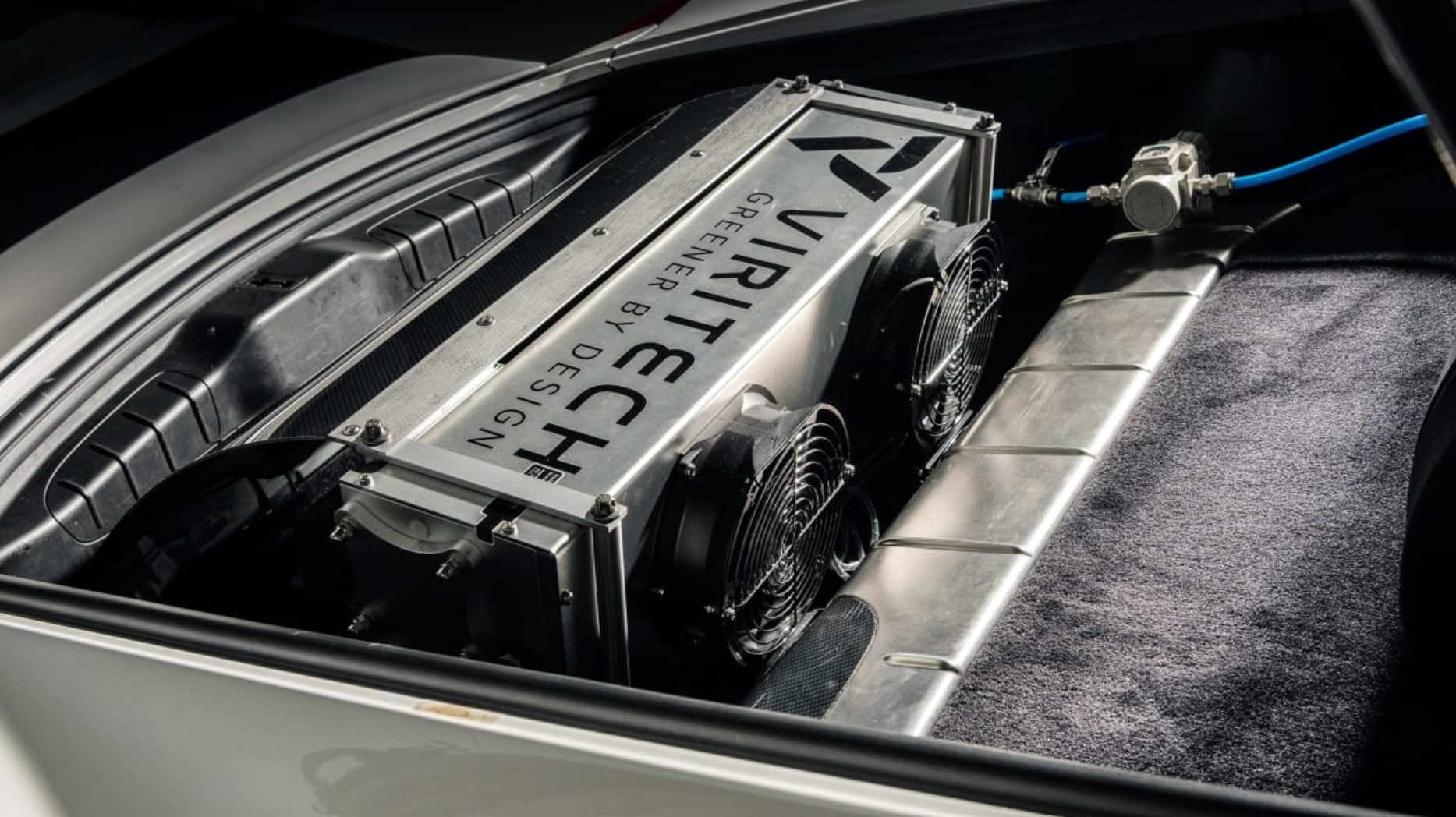

The Viritech powertrain is relatively easy to understand, but hugely complicated in detail. As is the norm with a hydrogen fuel cell system, hydrogen stored in a tank is fed to the cell, creating electrical energy and the only waste product, which is water. However, the Apricale’s stack, as it’s referred to, is used as a primary power source, not as a range-extender, and morevoer, it’s ‘turbocharged’ in that oxygen is forced in under pressure via twin compressors, raising power to 300kW. An interesting by-product of this is that it gives the vehicle it is fitted to its own authentic ‘voice’, rather than just the whine and artificial noises of pure EVs; it might even chuff and wheeze like a Group A touring car.

In traditional fuel-cell vehicles the hydrogen tank is simply bolted in, at the expense of weight. In the Apricale, the tank is used as a stressed part of the structure (meaning it effectively does two jobs), enabling the rear bulkhead of the carbonfibre monocoque to be much thinner than it would otherwise need to be. Many people still picture the Hindenburg disaster when hydrogen is mentioned, but as Faulks says, storing it in a tank safely was understood by the Victorians and their steam boilers, and Apollo used it on the moon. Every pressure vessel for hydrogen has a failure mode that means it leaks before it could explode, and the SAE has a clearly defined standard for filling tanks, unlike the myriad of chargers that sometimes make accessing the EV charging network befuddling.

So how is the rest of the Apricale’s four-figure bhp output produced? “We look at energy on the vehicle in a similar way to F1,” explains Faulks. “We have an electrical energy store, in this case a lithium battery with cells similar to an F1 car’s ERS set-up, so we have really high charge and discharge rates, and we can deploy up to 600kW when we need it, plus the 200 to 300kW from the fuel stack at the same time, so over 1207bhp (900kW) in total.”

As the Apricale’s range is in no way linked to the charge of the battery, the battery itself is small and light at 5.6kWh, and is always run in the zone where it’s at its happiest, so it won’t age or get damaged, unlike a traditional EV battery that has to put up with charge levels ranging from 100 to 0 per cent.

The energy management system that runs all this is christened Tri-Volt. It is perhaps the most complex and clever part of all. Essentially there are three operating modes. In urban driving or traffic congestion the Apricale (or a truck) is purely electric, leveraging all the advantages of such propulsion – quiet, high torque, zero emissions. For a truck, running in a connected environment and/or using GPS, the system will ensure the battery is full before reaching the area of slow-moving traffic. Mode two is steady-state running, where the vehicle uses just the fuel stack, thereby negating the need for the large and heavy batteries required by a BEV. And then mode three is where everything works together. In a truck that would be moving away from rest, or dealing with an incline; in the Apricale that will be for maximum acceleration, or running on a track.

Filling the tank with hydrogen takes between six and seven minutes, and there’s no plug-in element to the battery set-up, because the battery can harvest energy so effectively. It’s the opposite of a current hybrid car, where the dashboard display tells you energy is going back into the battery when braking hard but the range barely seems to move in the positive direction. The expected range of the Apricale is 480km in normal driving and around 320km when being worked hard on track.

Viritech’s home is a new unit just next to the flyover that spans MIRA’s high-speed bowl. Inside there is a dedicated electronics manufacturing department, a simulation room, a breakout area with fake grass and palm trees, and a workshop where currently two cars sit. One of these is the company’s first prototype, a 2009 Porsche Cayman with its flat-six removed and a fuel stack and basic tank installation in its place. It’s not a prototype for the Apricale as such, merely a test bed for the type of powertrain technology that the Apricale will use. In an amusing nod to the history of the Porsche marque, this stack is simply air cooled – unlike the Apricale with its intercooler and forced induction.

I drive the Cayman briefly, and perhaps the biggest compliment I can pay it is that it’s a non-event, almost silent, and smooth, which for a very first proof of concept is admirable. The long gearing (a carryover) means initial acceleration is sluggish, but once it gets going it’s swift enough, and you could easily use it to commute to work, or go to the shops. Its ultimate power isn’t quite up there with the ICE original, but that doesn’t matter (further development would take it there). Ths car’s job is to test the theory, and most of all to verify the work Viritech is doing on the simulation software that will enable its super-trick Tri-Volt system to manage the workings of the complex powertrain. The more data verified as accurate, the better and more trusted the simulations can be and the faster the development cycle.

The second prototype, based on a Radical that’s being stripped in the workshop during our visit, will have a much more representative powertrain inserted amongst its unsuspecting tubes, and looks set to be a rocket. Beyond that, Faulks aims to have the first proper Apricale, the XP1, up and running during 2022, with full production cars from 2023. Major technical partners should be named shortly, with a second round of funding imminent as well.

I’m trying to imagine what 900kW in a car that weighs under a ton might feel like. It won’t be like a Bugatti Chiron Super Sport or a 1500kW battery-electric hypercar; it might be a bit like a current F1 car or, as keeps coming to mind, that time when Mark Blundell took pole by over six seconds for the 1990 Le Mans 24 Hours when the wastegates on his Nissan R90C (900kg-ish, briefly 820kW-plus) jammed open. It’s not just the power-to-weight, it’s the relationship between power and weight that’s key.

The Apricales will be built to single vehicle type approval, the exact requirements for a hydrogen vehicle being worked out between Viritech and the government at the moment. It won’t have airbags or need to be fully crash tested, thus keeping costs realistic for a tiny company, but the monocoque is being built to full FIA LMP crash regs, so it will be exceptionally strong. The glint in Matt’s eye when Le Mans is mentioned potentially gives a clue to ambitions on the track.

We’ll bring you more of the Viritech story as it develops, but for now, the future of real driver’s cars suddenly looks that bit brighter.

Adam Towler