The 2023 Porsche Macan EV will cover more than 2.9 million kilometres of testing, but its life started long before that in a virtual world.

Before digital computing arrived on the scene, the next step in lifting ideas from the drawing board and turning them into reality was the building of prototypes.

Prototypes can be individual parts or complete cars, and once they’re built, they can be put through their paces to see how well they do and, in some cases, tested to destruction if necessary.

Traditional prototyping was a slow and expensive process because, even with the best engineers, theory wasn’t always borne out in practice. The constant back and forth between drawing board and prototypes was costly and enormously time-consuming.

Computer-aided design (CAD) and computer-aided engineering (CAE) for designing and simulating the performance of products changed things entirely, with the inevitable consequence that cars can now be engineered, prototyped and tested in a virtual world before any physical prototypes are built. Manufacturers can get closer than ever before to the finished result before prototypes roll into a wind tunnel or onto a test track.

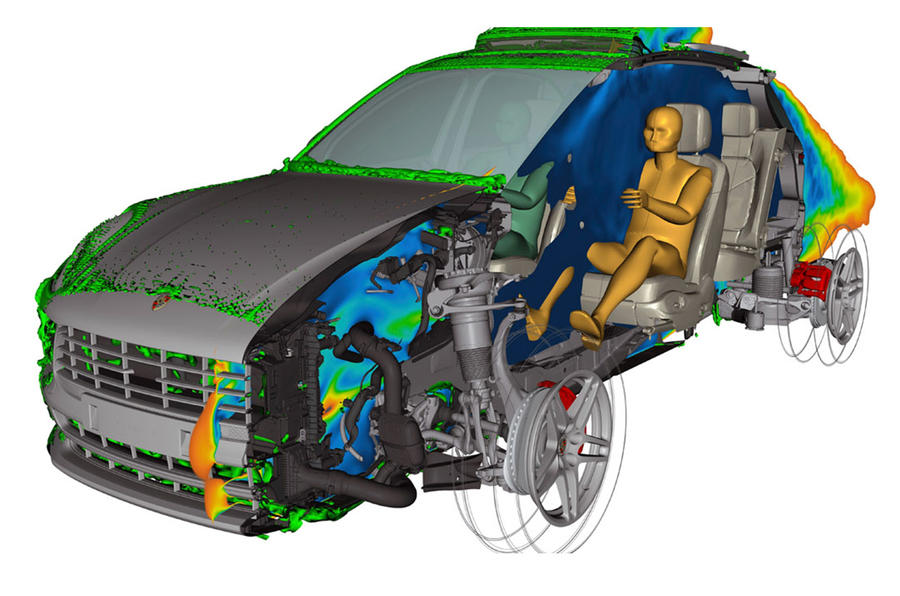

Porsche’s next-generation Macan is a good example. The company created 20 virtual prototypes for different purposes, from aerodynamics to energy management and acoustics. Their simultaneous use not only enables engineering teams to identify flaws but also to pick up design conflicts between the different disciplines as a complete virtual car is assembled.

With perhaps a greater than usual focus on aerodynamics to minimise drag and maximise the range of the electric sports SUV, the aerodynamics experts were able to get to grips with a virtual prototype early on. They began work on a flow-around model in around 2017, and the finishing touches are now being made on details like the cooling ducts. That’s right: virtual prototyping and simulation has now become so precise that it can take into account temperature changes on the performance of components and the car.

A less obvious aspect of the difference between EVs and conventional ICE cars has to do with the temperature control and management of the electric drivetrain – or, in engineering speak, thermodynamics.

An EV cooling system differs completely from that of an ICE car. A fuel tank needs no cooling, but a high-voltage drive battery needs careful thermal management. So do the electric motors and power electronics; modern combustion engines run at between 90 and 120deg C, whereas various elements of an electric powertrain operate at anything from 20 to 70deg C. Tuning the aerodynamics to eke out the range can be at odds with using airflow to cool components, which causes drag, so the two disciplines go hand in hand.

Prior to digital prototyping, rapid prototyping of vehicle components was in full swing. CAD driving multi-axis milling machines (machine tools) capable of creating complex forms from a variety of materials made it possible to create prototype components without going to full production tooling. It also became possible to make prototype manufacturing tools such as the dies (moulds) used to press body panels. They’re normally made at huge cost from high-carbon steel, but softer prototype dies can be made quickly from alloy and, although they’re short-lived, enable short runs of pressings to be made for evaluation.

So, digital and rapid prototyping has not only saved manufacturers money but also given us cars with fewer compromises.

Jesse Crosse