Nissan’s new e-Power hybrid might not be a revolutionary improvement to the petrol engine, but it shows that electric motors are here to stay.

The Nissan X-Trail and Qashqai are the brand’s first series hybrid models in Australia. The Qashqai is a front-driven hybrid, while X-Trail uses the car maker’s ‘e-4orce AWD’ system in Australia, which adds a second motor to the rear axle to give all-wheel drive.

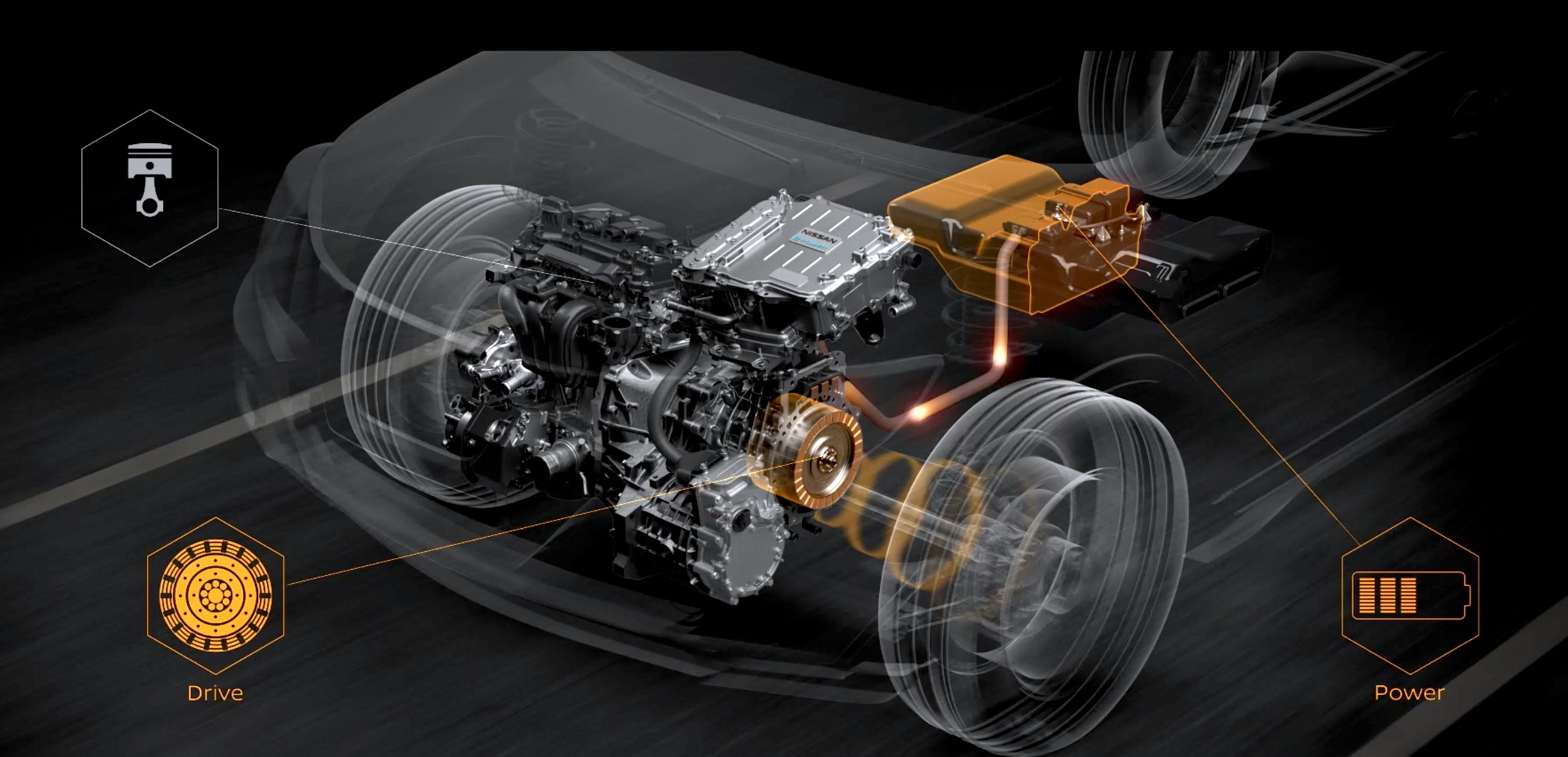

In both new hybrid SUVs, the wheels are actually driven by an electric motor only, with the engine acting as a petrol generator.

Lexus introduced a similar twin-motor all-wheel drive system in 2020 called Direct4. The marketing blurb highlights the advantage of adjusting handling balance by altering the torque of the individual motors. More at the front will promote power understeer, at the rear oversteer and a balance of the two neutrality.

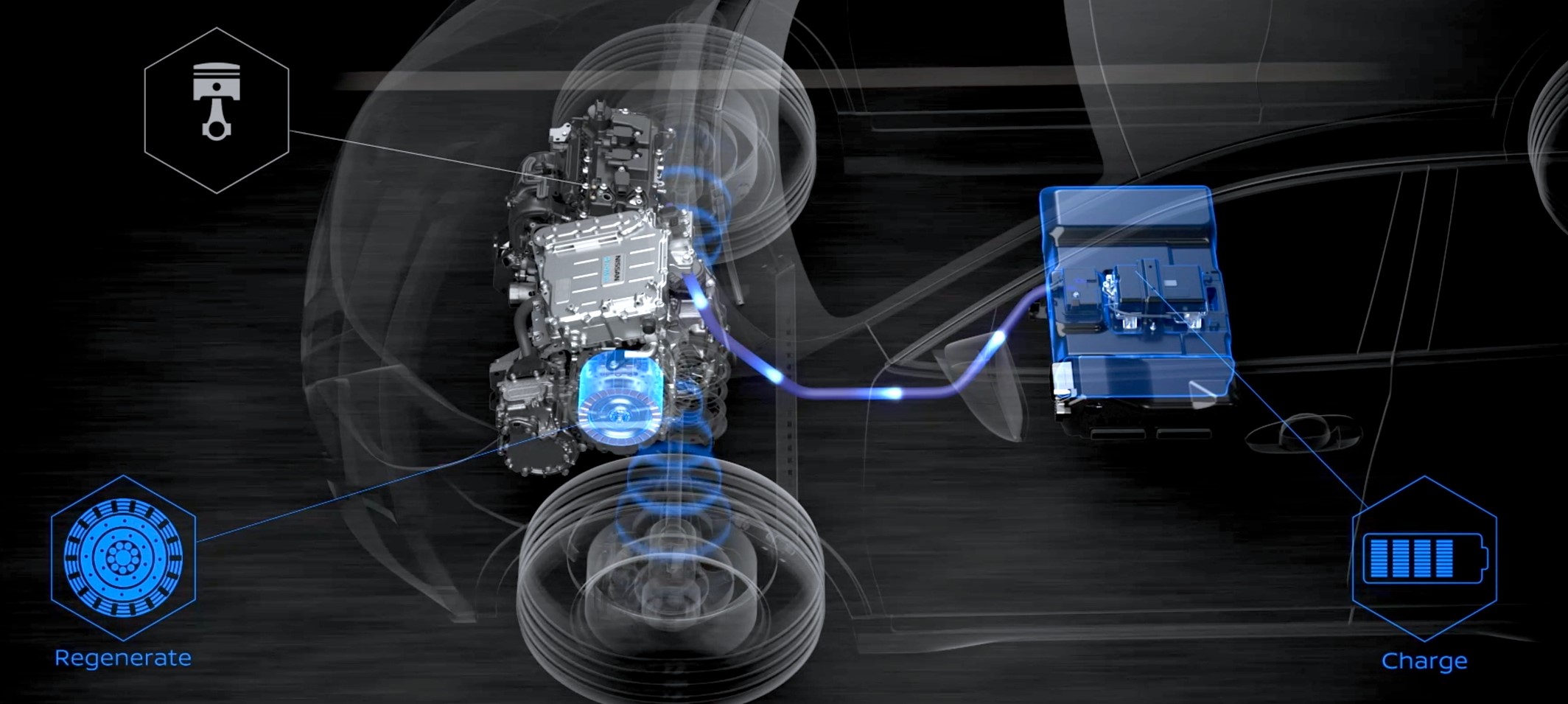

Nissan points out that by individually controlling the degree of regenerative braking at both the front and rear, instead of just at the front, the pitch of the car can be maintained with more of a level stance, avoiding the nose dive associated with any kind of braking.

Is any of that new? Nissan’s use of regenerative braking in this way may be innovative enough, although the fundamental idea of inhibiting dive isn’t and is usually dealt with through the basic design of the suspension geometry. You can even buy an anti-dive kit for the classic Ford Escort Mk1, but you can’t blame manufacturers for wanting to big up the plus points for their latest cars.

Distributing torque from front to rear and side to side, as Lexus is doing, isn’t new either and has for a long time been accomplished with a combination of mechanics and electronic control, including the choice of gearing in the driveline, electronic differentials, wet clutches and individual use of the brakes.

Changes in the torque output of electric motors can be instantaneous, though (or as good as), and Nissan says its twin-motor system is faster than mechanical all-wheel drive systems. That said, the reaction time of mechanical, torque-shifting systems is measured in milliseconds anyway.

But what these two new features do highlight is how many useful ideas can be squeezed out of electrified drivetrains as the technology develops, and without the degree of mechanical complexity needed with conventional drivelines.

Both systems also showcase what incredibly versatile things electric machines are. As well as doing away with tailpipe emissions, they generate maximum torque from the off, double as both motors and generators, act as powerful brakes as well, don’t wear out and don’t need servicing.

From early on in the evolution of modern electrified drivetrains, their ability to fill torque gaps in an engine’s performance has been exploited in hybrids to reduce emissions and fuel consumption while providing decent acceleration.

Coupled with an engine running on the Atkinson cycle, which is super-efficient but robs it of any transient punch, an electric machine adds the grunt needed for acceleration and generates electricity when slowing into the bargain.

Used in that role, you could even argue that electric machines make the combustion engine appear better than it really is.